Stop using the ‘delete’ button!

LAU instructor of photography Bassam Lahoud shares his vision of aesthetics and the future of photographic technology.

Students from Beirut and Byblos gather for an indoor photography class at Lahoud’s workshop in Amchit.

Lahoud received last March the Bulgarian Minister of Culture’s decoration from the Bulgarian Ambassador to Lebanon.

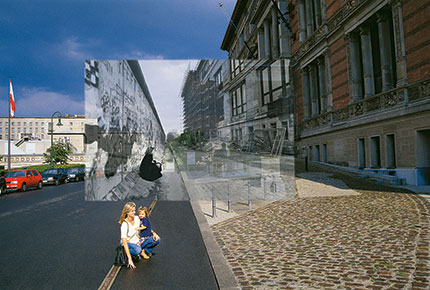

Using illustrator, Lahoud superimposed a picture he took of a Berlin street in 1984 (before the fall of the Wall) over another he took of the same street in 1998 with the same woman featured in both photographs.

In a 2006 tribute to a friend Lahoud used a Palm Treo mobile, first generation with 0.7 megapixel camera with a rotation movement.

Bassam Lahoud studied architecture and began his career as a photojournalist almost by accident. In 1974, he traveled to Greece and found himself in the middle of the Turkish-Greek war over Cyprus. With the borders closed, Lahoud could not leave and remained for a month and a half photographing the war as it unfolded.

“I only took a few pictures, because I could only afford film for a few pictures,” he remembers. Eventually Lahoud returned home, moving from one conflict zone to another, as the Lebanese civil war was rapidly escalating, giving him new material for his photo essays.

His approach, though, differed from that of most photojournalists, who rushed to the front lines and bomb sites. “You don’t need to show somebody dead, or someone with a rifle,” he says. “However, you can show the feelings of people, their character—the way they behave, what’s behind their eyes.”

Such approach Lahoud brought to conflicts around the world—from Serbia and Yugoslavia to Berlin before and after the fall of the Wall, to the Soviet Union and to Madagascar. Still, his art has not been limited to wartime photojournalism. He has documented architecture and heritage of villages throughout Lebanon, and of countries around the world that are regularly published in Lebanese magazine Prestige. Lahoud has also worked with oil painters to create multimedia projects, and produced Lebanon’s first exhibition of photographic nudes.

Like most professional photographers who prefer to remain “purists,” using only analog photography and avoiding the new technologies, Lahoud too is sensitive to the aesthetic and ethical problems presented by the ability to rapidly take thousands of pictures. “You can push the button lots of times and hope that you get at least one good picture,” he says. “But… The point of taking a picture is not to make a person beautiful, it is to take a beautiful photograph.”

Lahoud applies this principle in his teaching at LAU. “I teach my students to think, do a layout, composition, even if they are using digital cameras. In analog, you don’t see the picture as you are taking it, so you have to think. With digital you forget to think. But feeling that a picture is good and composing it is another—you have to do both.”

He also finds that the new technologies run the danger of cheapening photography as an art form. “I would say that 99.9 percent of people take pictures for no reason, maybe 1 percent take real, meaningful photos,” he says. “And selfies are awful.”

Lahoud is particularly offended by the ‘delete’ button. “When I take a picture, it stays. People often say ‘I don’t like it, please delete it,’ but this should be the decision of the photographer himself.”

Still, he concedes that a talented photographer can add a professional quality to any picture, regardless of the device. He has himself mastered mobile photography and recently exhibited a series of fine art photographs in a show titled “Mobile Art.” And Lahoud has caught the iPhone bug: “You can move with this device,” he says, enthusiastically about his iPhone6. Most recently he has been perfecting a technique he refers to as the “twist,” in which he carefully twists the iPhone device to capture a surreal, inverted mirror-image panorama.

“You still need to have culture, you need to be sensitive, to feel the subject,” he posits. “Otherwise, you will not succeed as a photographer.”

More

Latest Stories

- This Summer: Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Summer School for Middle Schoolers

- Into the Psychology of Justice

- Alumnus Zak Kassas on Navigation, Spoofing and the Future of GPS

- Hearing Between the Lines

- LAU Hematology Conference 2025: Advancing Science Through Interdisciplinary Exchange

- Dr. Chaouki T. Abdallah Invested as LAU’s 10th President

- LAU Guides Its Students Through the Code of Conduct

- Innovative Procedure at LAU Medical Center–Rizk Hospital Signals Hope for a Patient With a Congenital Disease